Last night, on a Spoleto stage in Charleston, a dazzling soprano flamed through a new one-woman opera, Emilie, based on the life of French mathematician and physicist, Marquise Emilie du Chatelet. She, whose translation of Newton’s Principia Mathematica is still used today; and whose Discourse on Happiness fleshes out a woman’s sensual path to joy, took Voltaire as her lover of many years, as well as other men of great minds with whom her atomic powers collided. Her thirsty lust for life harbored, within it, a strange foreboding of an early death, even as her fourth child grew in her womb. True to her harrowing dreams, Emilie’s expansive, solar kind of life ended in childbirth, in 1747.

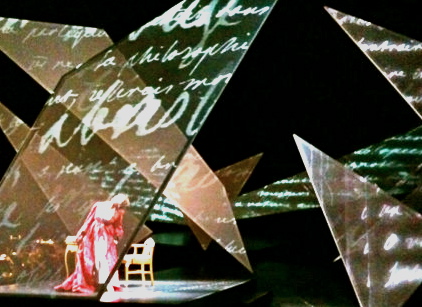

On the opera stage, enormous geometric screens filled and emptied with scribblings of calculus, math equations, love letters; the science of moon and tides, of sun and desire. Her quill scratched madly into the night in an urgent effort to finish her translations before fate stepped in.

I miss the colors already, she sang so plaintively, that I did, too. The scientist explained her treatise on how colors meet the eye, how violet and gold mate in the mind, and yet stay distinct from one another. Her writings seem adequate to both science and love – she touched them with the same curiosity. Caressing her crimson robe, the philosopher challenges: If God has given us pleasure and suffering, then why must we honor him only with our suffering? Why not our pleasure, as well? This blood hue of red, like the breath of her lover, was a pleasure to her – one that brought her closer to the pulse of God.

At the end of the opera, Emilie walks slowly, daringly slow, up a steep incline to the rear of the stage, her back to us in the dark. Only the far side of her face is lit by the flames of a roaring sun into which she is drawn. She is silent at last, feeling the colors passing through her, as Marge Piercy put it: all the colors of the world pass through our bodies like strings of fire. The immense indigo night, the yellow flame in her lover’s eye, the red blood she will spill.

I want. I want to live all of these colors through the prism that I am; the pleasure and the suffering alike lending their angle and hue; and make of them, as I can, a blazing happiness. And then, when it is my time, I want to walk as she walked — bravely and silently — into the roar of many suns. Into the vast sum of universes. I want to walk, at last, into the light which receives all colors and worlds back into itself, as a sun enfolds its flames.

And then flings them back out again – leaping, boundless, forever – into the open sky.

*Marge Piercy, “Colors passing through us” from Colors Passing Through Us (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003).